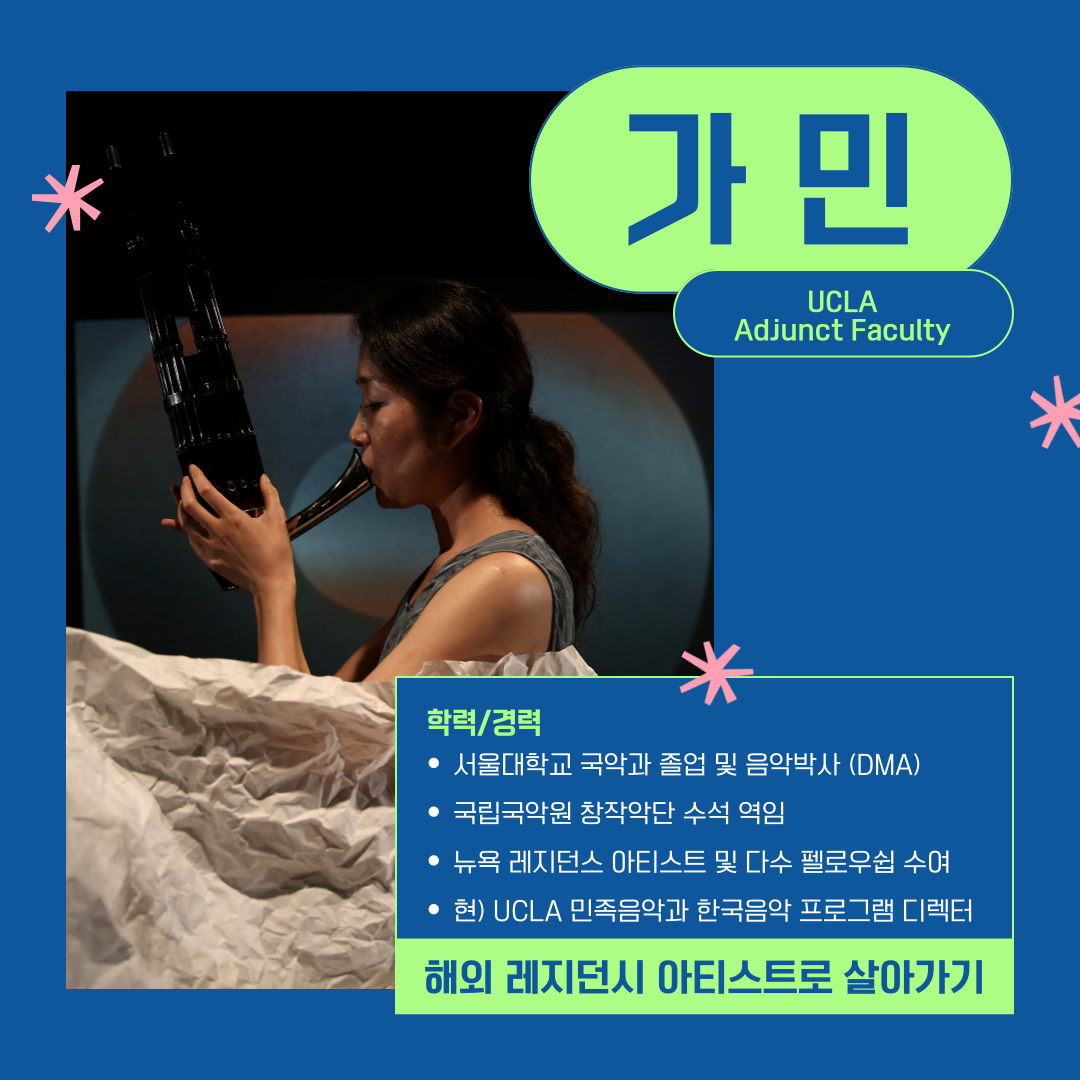

Gamin - Piri Performer / Director of Korean Music at UCLA

Hyunchae Kim: Is there a reason you perform under the name “Gamin”? What does “Gamin” mean?

Gamin: I started using a stage name in 2008 when I released my album under the name Gamin. Ever since I was young, I wanted to have a different name, and I liked the meaning of gamin—“beautiful” and “jade stone.” I started using it, and now it has become my legal name. Especially when I began working overseas, “Gamin” felt natural and fitting.

Hyunchae Kim: How did you come to move your performance base abroad?

Gamin: While I was working in Korea as a member of the National Gugak Center, I had the chance to perform in the U.S. and Paris. I experienced a huge cultural shock at the time, and I returned to Korea thinking, “I have to come back to that stage someday.” Three years later, I was selected by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism as a New York residence artist, and as I began working in New York, my base naturally began shifting there. As I experienced different kinds of music and performed contemporary music—which I loved and was already interested in—my artistic foundation moved naturally as well. Still, I never felt I had “left” Korea. For the past 14 years I have always traveled back and forth between Korea and the U.S., and I continued performing in Korea. Life as an independent artist has many challenges, but I feel joy through the act of creating.

Hyunchae Kim: You were principal piri player with the National Gugak Center’s Creative Orchestra and also had an active solo career. Did that domestic experience help with your international activities?

Gamin: My career in Korea was an important part of my musical life, but when starting fresh in a new place, those experiences didn’t feel particularly important. What mattered more was having the mindset of beginning anew. My time as a New York residence artist was my first experience abroad, so it left the strongest impression. I planned my own projects, visited performance venues and galleries to propose ideas, and collaborated continuously with new artists I met—some of those projects continue even now. Looking back, the residency in New York was an unforgettable turning point where I lived freely and accumulated many musical experiences, but many other experiences have also been precious in their own ways.

Hyunchae Kim: In what ways are the U.S. and Korea different in terms of working as an artist?

Gamin: To answer that, I think I need to go back to 2011 when I first began my residency. At that time, there were very few freelance gugak musicians. Most musicians worked within orchestras, and independent activity was rare. But seeing the activities of younger musicians now, new programs and opportunities have grown a lot. These days, there are many ways to sustain a career as a gugak musician without going through the orchestra system. Even though I had my own solo activities, the idea that one could work independently outside the orchestra felt refreshing.

And in terms of creative gugak and contemporary music, the concept of “Korean music composition” was more limited back then. In New York, when I jammed with improvisers, the genres were extremely diverse—it felt new and exciting. At that time, improvisation wasn’t considered part of Korea’s “creative music” sphere. In fact, 15 years ago, even the idea of playing saenghwang with 24 or 37 pipes was seen as a side major. Because of Korea’s educational system, focusing on only one thing was strongly emphasized. Now the trend has changed a lot.

Improvisation is trendy again now, but at the time, if I did improvisation in Korea, people would say, “You read scores so well—why improvise?” They thought improvisation was something people did because they couldn’t read music. The view of creative music was narrow.

My experiences with music outside of Korean music were much broader and more diverse, and they allowed me to try many new kinds of music without hierarchies. Also, because of Korea’s historical and cultural inferiority complex, people would verbally emphasize pride in Korean music, but in reality—even Korean musicians—aren’t very interested in gugak. It exists in an environment where people don’t feel a need to know it. Outside Korea, however, in spaces with diverse cultures, I felt that interest in Korean music was higher. Of course, discrimination exists in the U.S. too, but there is a general attitude of valuing diversity, and I felt more respect for different kinds of music.

In Korea, very few composers show interest in writing for gugak instruments, but in the U.S. many composers are curious about writing for instruments from different cultures. In Korea, although many composers technically operate as freelancers, I don’t think the performing arts ecosystem is robust. Most performances rely on institutions like schools, associations, or research societies. Compared to that, what I experienced in New York felt much more diverse and independently driven. Artists have more freedom in the substance of their work and are not tied to institutional directions. The possibilities are more open.

I always carry titles like “former National Gugak Center member,” but outside Korea, my titles became more diverse. Besides performing, I also play a mediating role in introducing and teaching Korean music, which pushes me to research, reflect, and work harder. The expectations placed on me have expanded.

Hyunchae Kim: You didn’t attend school here nor belong to an institution; you’re working purely as an independent artist. How did you build local connections?

Gamin: For those who studied here, their schools become a major network, and that can be very important. But I had none of that. Since my work is based on music-making, most of my collaborations have been with individual artists. Someone might introduce an artist and we meet to jam—artist to artist. I also meet people when I attend concerts or when people come to my concerts. That’s really all.

But it’s not something that happens just because I want it, nor just because they want it. As experience accumulates, naturally you find people to work with, and from that more opportunities arise. I’ve never had management nor been affiliated with any organization. That, in itself, shows how strong and independent the arts ecosystem is here. Your activity can be sustainable even without being tied to a school or association. Many artists arrive in New York from all over the world without knowing anyone and start the same way. It might be a unique condition of New York rather than the entire U.S.

Since music happens through people, I think what matters is cherishing each small encounter. In the music community, one person knows someone you know, and relationships form naturally. Yes, sometimes I have pursued opportunities actively, but more often it was the small, accidental encounters that led to big connections. A single audience member could invite you to perform or introduce you to someone. That happens quite often.

Hyunchae Kim: You are currently the coordinator for UCLA’s Korean Music program. Could you introduce the curriculum?

Gamin: My official title is Director of Music of Korea—in other words, I’m a lecturer. UCLA’s ethnomusicology program is the oldest in the U.S., and accordingly, it is quite large. There is an Ethnomusicology Department and a separate Music Department. Since the 1950s, the school developed many world music ensemble courses. The Korean Music Ensemble was active for a long time as well, but was discontinued for about 10 years until it was revived when I arrived.

Although I’m technically faculty, since the 1990s the ensembles have been run independently through their own funding. So some ensembles have disappeared and about 15 currently remain, each with different circumstances. Without funding, it’s difficult to operate, and even now resources are insufficient, so we are continually looking for solutions.

Music of Korea is a practical, hands-on class where students are introduced to various Korean musical genres and practice and perform on instruments. We don’t have many—some gayageum, samulnori instruments, and piri—so students learn and perform with what’s available. Many students have no background in Korean music; some aren’t even music majors. I have to think carefully about how and what they should learn. UCLA uses the quarter system, so each term is only 10 weeks, and our instruments are few and in poor condition. Nevertheless, the important thing is that students learn Korean culture through Korean music.

Even if they learn just a few simple folk songs, form an ensemble, and experience performing on stage, that’s meaningful. Sometimes we connect with the local Korean community and take field trips. The focus is on connecting with Korean culture.

Hyunchae Kim: Many people want to come to the U.S., but visas make it difficult. What kinds of visas can artists use, and what are their pros and cons?

Gamin: For long-term stay, the O-1 artist visa can be obtained for one or three years. For short-term performance visits, the P-3 visa is available, and for research or exchange programs, the J-1 visa. Each visa matched the purpose of my stay at the time.

I received the J-1 visa because the Asian Cultural Council sponsored it through a fellowship. After that ended, I applied for an artist visa through self-petition. Now I have a green card, which I also obtained without a sponsor, through self-petition. I’ve also briefly used performance visas for short visits to Korea.

For the O-1, like the green card application, I compiled documentation of past activities and future plans. Since I traveled to Korea every year for almost 10 years, I initially thought a visa would be better than a green card, because green card holders have limitations on extended stays outside the U.S. Later, during the pandemic, I obtained my green card. I didn’t want the restriction of having to stay in the U.S. for six months each year. I wanted the freedom to spend several months in Korea or travel extensively for tours. Many people relocate fully from Korea to the U.S., but in my case, I wanted to move freely. Over about 10 years, as my artistic activities grew increasingly different from what I had done in Korea, my center naturally shifted toward the U.S., and I ended up receiving my green card.

Hyunchae Kim: Finally, a message for younger artists who dream of working in the U.S. And please recommend any programs you think are good.

Gamin: For young musicians, I highly recommend creative programs such as the Omai Residency, which many Korean artists have participated in, and the Silkroad Ensemble’s annual Global Musicians Workshop. I encourage you to experience the wider world as much as you can. Follow what your heart desires. The preparation you need is mental preparation—your own desire, curiosity, longing for something new, the urge to search for something. That is the most important thing.

This isn’t about location. You don’t change just because your location changes. What matters is your mindset—your openness and how you see the world. That’s what will allow you to adapt to a new environment and discover what you love. Nothing magical happens just because you physically relocate while everything inside you stays the same. Of course, you don’t need to change everything—your core remains—but when you encounter a new world, your flexibility determines how positively you can receive new experiences.

Hyunchae Kim: Gayageum player / educator. Current resident artist at the Korean Performing Arts Center (KPAC) Chicago; Director of Stringway.

Gamin: Piri player / educator. Former member of the National Gugak Center Creative Orchestra. Current Director of UCLA’s Korean Music Program.