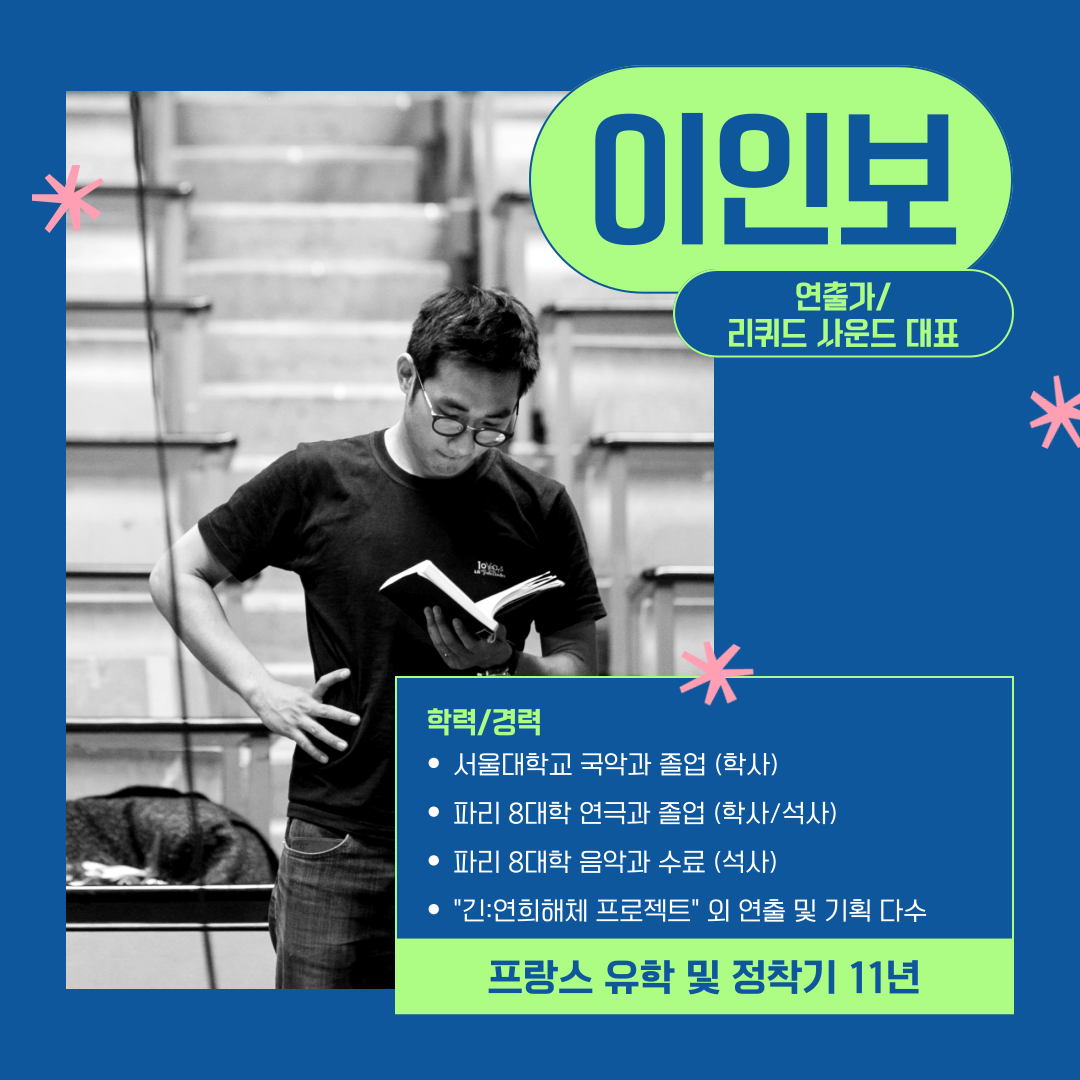

Inbo Lee - Artistic Director / Director of Liquid Sound

Hyunchae Kim: How did you decide to go abroad to study?

Inbo Lee: I wanted to create performances, and I realized that to make the kinds of performances I envisioned, I needed to study directing. Why did I have to go abroad? I didn’t analyze it step by step or make a detailed plan—I just suddenly felt I needed to go. I prepared for about three years, wondering where I should go, and while I was in the military, a friend who had lived in France told me that tuition there was free, and I was tempted by that (laughs). While in the military, I started doing research little by little, visited study-abroad agencies, and attended a language institute. At Seoul National University, there was a class called “Performance Creation Practicum” taught by a directing professor. When I asked him for advice, he said that France had an experimental spirit and might be a good fit for me.

Back in college, when I was part of the Youth Orchestra, I realized that many people—sound engineers, lighting designers, costume designers—are needed to create a performance, and that made me think directing might be right for me. Around that time, a classmate once asked, “Are people who do gugak (traditional Korean music) really artists?” And I couldn’t immediately say, “Of course!” I later wondered why I couldn’t answer confidently, and that led me to think more deeply… I think I used to believe that artists were people who created or made something. If someone were to ask me that question now, I think I could say yes—although sometimes there are exceptions. I also want to be an artist myself, and I’m working toward that.

Hyunchae Kim: Do you have your own standards for distinguishing between artists and those who work in the arts but are not artists?

Inbo Lee: There are people who “shine” and those who don’t… It’s a very personal standard, something I keep to myself, but some people just have a sparkle in their eyes. They aren’t habitual in their ways; they keep changing and aren’t trapped by time. Whether they’re performers or not doesn’t matter—there are planners and educators who shine too. People who sparkle look better to me than those who spend their days onstage in shades of gray. If you ask whether I consider anyone who shines in everyday life an artist regardless of their job, that’s when we’d need to have a deeper conversation about what art is.

Hyunchae Kim: You majored in daegeum as an undergraduate, but in France you studied directing, right?

Inbo Lee: Yes. First, I transferred into the third year of the Theatre Department at Paris 8 University, finished my bachelor’s, and then completed a master’s in theater. I was considering a doctorate, but my professor told me that a PhD is mostly theoretical work, and suggested that, since I had performed music in Korea, I should continue in the path of making performances. My master’s thesis topic also influenced things—it was titled “Music and Video Used on Stage,” and explored how music is used when it combines with other arts, not just as a concert. Since that aligned with my interests, my professor advised me to continue in performance-making. So I re-enrolled at Paris 8 in the music department to study computer music and finished that program. Afterward, I moved to Paris 3 University and majored in médiation culturelle—which in Korean would be something like “cultural mediation”—where I studied planning, promotion, and related subjects.

Hyunchae Kim: You studied and worked as an artist in France for 11 years and returned to Korea in 2021. Was there a particular reason?

Inbo Lee: After finishing my studies, I managed to obtain a three-year artist visa, which was difficult to get, but it wasn’t easy to sustain artistic work there. In Korea, things were comparatively more convenient—if I needed a gayageum, for example, I could access one more easily… But coming back to Korea takes as much effort as going abroad. I had been traveling back and forth, and for me, Korea had more advantages. In France, there are more artists, and the gap between professionals and amateurs is quite large. It’s very hard to enter the professional field. I wanted to get formally invited by theaters, but it wasn’t easy. So I thought it might be more effective to create strong work in Korea that overseas presenters would want to import. Personally, my first and second children were born and being raised in France, and when my third was about to be born, COVID hit, and I decided it was time to return to Korea.

Hyunchae Kim: What are some differences between living as an artist in France versus Korea?

Inbo Lee: The culture is very different. There, people try to live together, and there’s a lot to learn from that. Whether someone is slow or fast, the country as a whole moves at a slower pace than Korea; it’s a culture where diverse people try to coexist. “All citizens are equal before the law” is Article 1, Section 1 of the French Constitution. A small example: when my son went to school, they asked whether he eats pork. Because people of many backgrounds live together, respecting differences is something they practice daily. It may feel inconvenient or unnecessary at times, but I think it’s an important strength of their society.

Another example: once there was a proposal to start charging foreign students tuition. Surprisingly, local French students protested, saying that foreign students also deserved equal educational rights. In Korea, we might think it doesn’t concern us and move on.

The performance culture is also very different. Many performances are experimental—or outright failures. There are shows that are messy or unfinished, yet people still pay to see them. The audience mindset is different. When I worked at a dumpling bar, I once asked a customer if the performance he saw that day was good. He said, “If even two out of ten shows are good, this month is a success for me.” People still go because they’re curious: What is this artist trying to do? Why are they doing this? They wonder about the motivations behind the work. In contrast, in Korea we place great importance on perfection. That's something I’ve been thinking about lately: Is the perfection we pursue in Korean society obscuring something more essential? Are we missing things because we’re so focused on perfection? We invest so much time and effort in achieving perfection that perhaps we overlook other things. In France, many performances give up on perfection, and audiences accept that, which shifts the focus more toward what the artist is trying to say.

Hyunchae Kim: How did you study French? Did you struggle with language barriers?

Inbo Lee: Before enrolling in school, I attended a language academy in Jongno. After finishing my military service and returning to university, I took French classes there as well. I earned the A1 and A2 certificates in Korea, then attended a language school in France for about seven months. Usually, you need B1 or B2 to enroll in university. I earned B1 and applied to Paris 8. They accepted me on the condition that I continue language study while enrolled, so I took university language classes alongside my coursework. Language is always difficult, but France is a multicultural country and quite open. Once, a friend even told me, “I’m sorry I don’t know your language.” Of course it’s great to speak perfectly, but I don’t think we should wait until we’re perfect before doing the next thing. You’ll never be perfect anyway. What matters is continuing to do what you want while learning. The language you learn in language school and the language you need at university are different, so experiencing things firsthand and learning through real encounters is more important.

Hyunchae Kim: How are you different now compared to before you went to France?

Inbo Lee: My identity has changed. Before, I was “someone who plays the daegeum.” Now, I’m a “director.” But I wondered: when does one become a director or an artist? When talking with other directors, I once said that the threshold feels low. I think my identity as a director formed around 2010; before that, I felt like I was floating in space. As a daegeum player, I used to think constantly about how to produce a particular sound, how to play well. After going abroad, I saw how people who call themselves artists actually work. I watched a lot of performances—not only music but especially dance.

My perspective on performance broadened. A director needs to see the whole picture, like looking down at a soccer field from above. I also had to communicate with more people. When speaking with musicians, I used certain vocabulary and discussed certain ideas; with lighting designers, the language and content were totally different. That’s natural given the different roles. Even when watching traditional music performances now, I perceive them differently. Before, I cared about whether a note was correct, the volume, and how polished the performance was. Now, I question what “finished” even means and whether it really matters. Does sitting versus standing change something? For some people, that matters a lot. But I wonder if there are things more important than that—or equally important. Movement, visuals, creating space, what state the audience should be in—everything beyond sound. The things we’ve traditionally considered important are important, but maybe we’re missing something by thinking they are the only things that matter. I ask myself those questions often.

Hyunchae Kim: After returning to Korea, what have you been working on?

Inbo Lee: In 2016, I began directing under the name “Liquid Sound” in France. After returning to Korea, I continued working as Liquid Sound with a choreographer, director, stage designer, and composer, exploring how we view traditional Korean arts. I wanted to broaden the artistic scope of traditional arts—to dance, street theater, visual art, performance art, and so on. Ultimately, if we are making art now, we are creating “contemporary art.” But the question “What is contemporary performance?” is something other art forms have already asked and resolved. If there is contemporary fine art and contemporary dance, then what is contemporary gugak? What do they value? Are we continuing tradition, or trying to break away from it? After grappling with these questions, my conclusion was: “Let me create performances that I can see.” And then make them accessible to others. I work with tradition not because it’s the most beautiful, but because it’s the easiest medium for me to express myself—it’s the language closest to me, the one I’m most comfortable with. Even though I am a director, I remain fundamentally Korean, and similarly, my roots in traditional arts never disappear.

Hyunchae Kim: What projects are you focusing on now?

Inbo Lee: I just did a showcase yesterday for a piece called Snow Fragments, which is based on traditional vocal genres like pansori and jeongga. The project name is “Sound Space.” The “pan” in pansori refers to a kind of space, and space is extremely important in contemporary music. I’m exploring how to create spatial perception sonically—what historical spaces meant, what contemporary spaces mean, and how we can interpret them. In pansori, the key narrative sections are called “nundaemok” (eye sections). I started wondering: Are those sections still the important ones today? Maybe what is “important” has changed. In pansori, the most important element is narrative, but I began thinking that by focusing on storytelling, we might be missing other things. So I removed the narrative entirely and reinterpreted the material musically, using pansori and jeongga to create spatiality, then rearranged them into this new work.

Hyunchae Kim: Gayageum performer/educator; currently Resident Artist at the Korean Performing Arts Center of Chicago (KPAC); Director of Stringway.

Inbo Lee: Director; B.A. in Korean Traditional Music, Seoul National University; M.A. in Theatre, Paris 8 University; current Director of Liquid Sound.